Students acquire language by practicing it. Speaking and listening often come before reading and writing. Practice the language you eventually want students to read and write by providing structured opportunities for listening and speaking in class. For example, when having students talk “with an elbow partner” or during a “think-pair-share” discussion, consider posting sentence frames for discussions and giving explicit instructions about who should speak first and how each partner should respond.

Students acquire language by practicing it. Speaking and listening often come before reading and writing. Practice the language you eventually want students to read and write by providing structured opportunities for listening and speaking in class. For example, when having students talk “with an elbow partner” or during a “think-pair-share” discussion, consider posting sentence frames for discussions and giving explicit instructions about who should speak first and how each partner should respond.

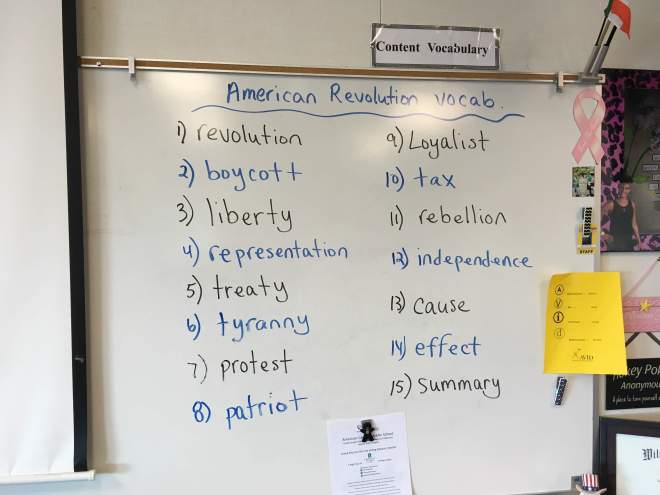

What are Tier 1, 2, and 3 Words?

Sometimes people label words Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3. Tier 1 consists of everyday words used in casual, informal conversations, such as “tell” or “like.” Tier 2 (also called Academic Vocabulary) includes words used in academic settings that are not isolated to a single discipline or content, such as “effect” or “summary.” Tier 3 words are discipline specific words such as “simile” or “erosion” or “Loyalist.”

Often words have multiple meanings, and may have discipline specific meanings, such as the word “formula.” Many students may not recognize that a word has different meanings depending on the context. For example, if you are using the word “formula,” you may want to spend some time reviewing its multiple meanings and let students know which meaning applies to your lesson or assignment.

Further reading:

Empowering ELLs Blog: Tiered Vocabulary: Not All Words Are Created Equal

Bright World Adventures: Tier 1, Tier 2, Tier 3 — What?????

Focus on What’s Working: One-on-one Conferencing

As an ELD teacher, I have a deeply held belief and commitment to student collaboration because I know how vital practicing language aloud is to supporting language development. Unfortunately, given the current conditions of hybrid learning, I have had almost no success with student collaboration.

Rather than focusing on what’s not working, I am shifting my focus to what is working and getting better at it. This is asset thinking in action. Our students have strengths and so do we. Let’s use that knowledge to foster learning.

Strategy Focus: One-on-one learning chats with students.

- Co-construct success criteria for the unit/project/assignment you are working on. Students can look at exemplars and then build a list of what makes the work high quality. Pick 3-5 of the most important items on the list as your success criteria.

- As students are working, have students self-identify one criterion for which they would like feedback.

- Conference with students one on one. Give them feedback on the ONE criterion they have self-selected. Move quickly so that you can maximize your opportunities to meet with students one on one.

One of the most powerful tools you can use right now is one-on-one conferencing. Students miss this type of interaction with teachers. They crave affirmation and feedback. Students often report that this is their FAVORITE thing teachers can do. So, if you can, make time and space in your hybrid classroom for it!

I look forward to when I can make collaboration a central part of my teaching strategies again, but, for now, I am going to utilize other methods for encouraging students to keep engaging and keep progressing.

“But they had so much time to finish that…”: Getting Students Unstuck

It’s a familiar scene. I’ve given my students ample time, tons of resources, and lots of instruction. Now all they need to do is create a product that shows and applies their learning. They are in groups so they can help each other. They have access to and know how to find the resources I gave them. Yet, despite my multiple attempts to redirect them to the task and extending the work time for far longer than I had originally allotted, some or most of the groups are producing little to no work. When I ask the students, they say they need more time, but the more time I give them, the less they actually produce. Everyone is frustrated and I am exhausted from running from group to group putting out fires and redirecting behaviors. What’s going on? Below are eight areas to explore with corresponding questions to help you discover answers:

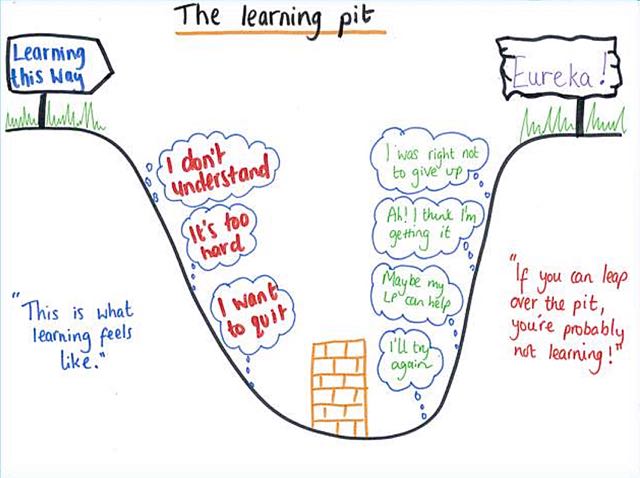

- Culture & Mindsets: Have you cultivated a classroom culture where mistakes are seen as valuable information and struggle is seen as part of the learning process? Have students had multiple opportunities to experience incremental and meaningful successes, to bolster their self-confidence and help them to fight back against the internal and external voices telling them they can’t? Do they believe that they can learn and that learning is worth the effort?

- Clarity / Exemplars / Rubrics – Do student know where they are going in their learning? Do they know where they are right now? Have them identified their next steps? Can they tell you and each other? Can they use exemplars and rubrics (or success criteria) to evaluate their own work and the work of their peers?

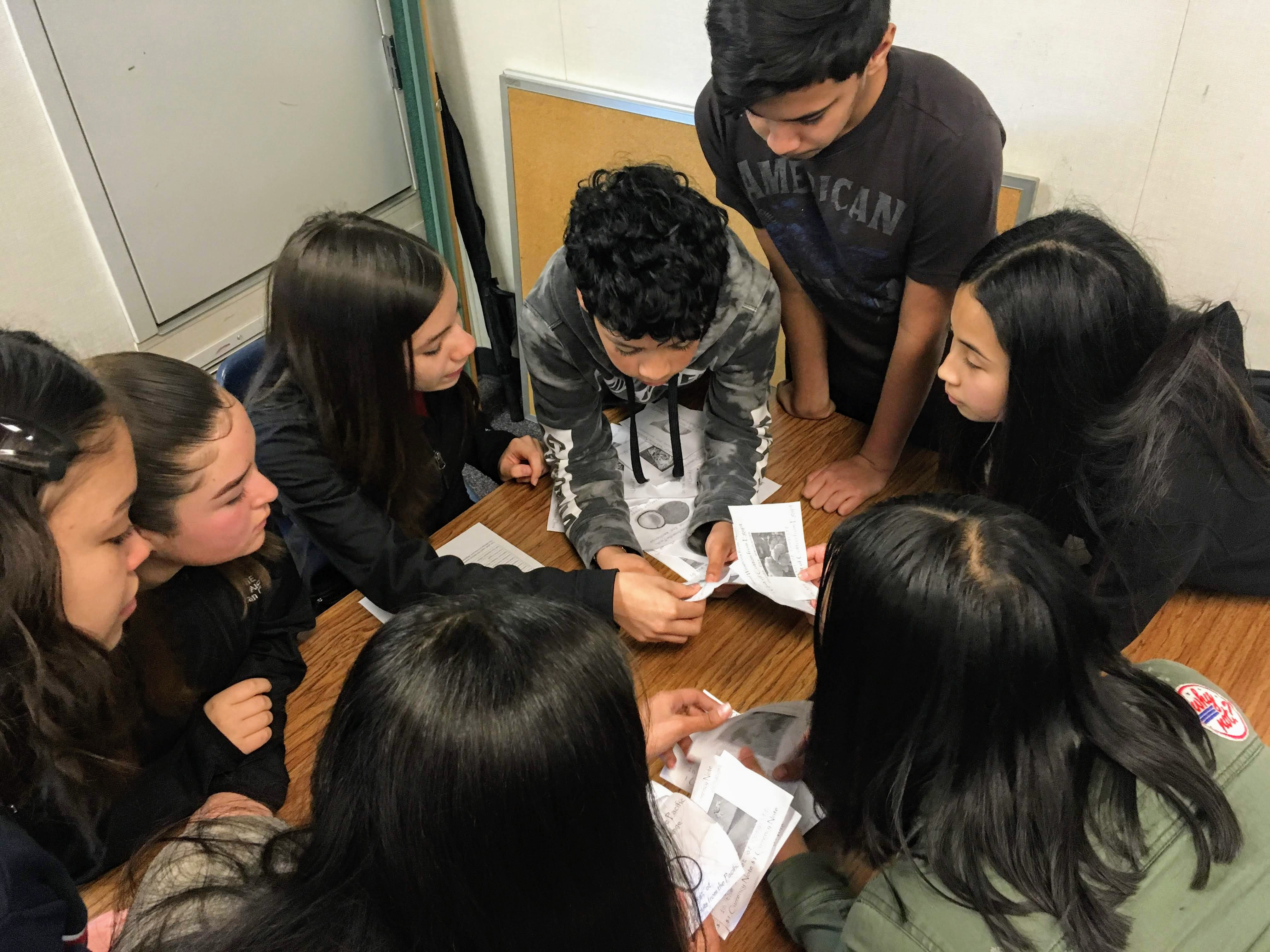

- Group Work – Do students know how to work in a group and why they are working in teams? Do students make use of norms, roles, protocols, goal/intention setting, and reflection as part of the structure of their work in teams? Do student-leaders have strategies to support their peers without telling them the answers or doing the work for them?

- Pacing / Modalities – Have you chunked the time to allow students to remember where they are in their learning and what their next steps will be? Does the pacing and chunking of time of your class account for the need for students brains to “cycle down” approximately every 15 minutes? Do you incorporate multiple ways to pause and process information, such as using movement, visuals, or talk, so that information can be digested and retained?

- Teacher-guided Reporting – Are your questioning techniques such that students are doing the thinking and planning, and you are guiding them through that process, or do you find yourself being prescriptive and directive? Is your goal to find out where students are in their learning or simply to get them back on task? (Pro Tip: Simply telling students what they should be working on and then walking away does not work!)

- Scaffolds- Are students using scaffolds effectively? Do they know how to use the scaffolds you have provided?

- Accountability – Do you regularly use various forms of public sharing of goals and progress that are not shaming but are motivating? Do you track students’ contributions to team and class discussions? Do you use randomizers when questioning the whole class or some other way to keep students “tuned in”?

- Surface, Deep, and Transfer Knowledge – Do students have a surface level understanding of the basic vocabulary, concepts, and processes need to complete the assigned tasks? Have you given students tools and protocols to help them relating concepts and ideas at a deeper level and to process information? Are students ready to attempt apply their knowledge to new contexts? Can your students accurately self-assess where they are in their own learning process?

So, that’s A LOT, I know. After doing several rounds of observations with teachers using the ELL Shadowing protocol, these are the eight areas that seem to capture the emerging themes of our learning. Choose one focus area and try something! Need more specific ideas about how to do that? Reach out and let me know!

“What are my students saying?”- Three Ways to Check In

I visited a math class this week that was focusing on academic discussions. Whenever your let students talk, there will always be some off task conversations. Collaborative classrooms are noisy and can even feel chaotic during group work. This causes the control freak in me to freak out. So, what are some effective strategies for monitoring academic discussions?

When engaging in collaborative activities teachers must attend to student mindsets and classroom culture. Groundwork needs to be laid so that students are willing to take risks in front of each other and so that they “buy in” to the work. With that said, here are four simple tips focused on monitoring:

- Create a structured note taking guide and discussion protocol.

- While students work, stand near to groups and scribe what they are saying. (Alternatively, you could use a device / audio recorder, like a phone or tablet, on the desk to record student conversations while you rove around the rest of the room).

- Before, during, and after a collaborative discussion, leave time and space for students to reflect on both the content and the process of the activity.

Need to Differentiate? Just Jigsaw it!

Sometimes the task of differentiating learning can feel really daunting. We have students with a wide variety of abilities and traits. How can we design learning that simultaneously meets their needs and doesn’t take forever to plan?

When I first heard about differentiation, I thought it meant I had to create a bunch of different activities and worksheets for the students in the my room. Just the thought of it made me want to quit before I started. Now I realize that a lot of the differentiation can be embedded in the learning strategies and routines I implement.

Enter the Jigsaw Method. Maybe you were introduced to this method in teacher school, like I was. Essentially, you chunk the work into sections. “Expert groups” learn about their assigned section together. Then, one member of each expert group returns to their “home group” and shares what they learned. Usually, the teacher supplies a graphic organizer, a notetaking guide, or question handout. The entire lesson wraps up with a quiz that includes material from every chunk of work, thus reinforcing accountability and on-task behaviors.

In order for this strategy to be effective for English Learners, the group work itself may need additional layers of structure or support. Think about this example: I want my “expert groups” to read and discuss a section of the textbook and then summarize the main idea and key details. To guide this process, students may be assigned specific roles while in their groups. I may provide a handout with discussion sentence starters that we use regularly in class that provide the academic language I would like them to practice while they are in their groups. I may need to give specific instructions about whether or not to read the section aloud, who should do the reading, and what they should do as they read.

The Jigsaw Method does not guarantee that students with stay on task or complete the work. Students may need additional guidance in order to access the curriculum. But if you are looking for a structure that lends itself to active learning and differentiation, Jigsaw is a great place to start.

Here are some additional resources to help you prepare a Jigsaw Lesson. Let me know how it goes!

- “Jigsaw Method” (How to Video)

- Cult of Pedagogy “4 Things You Don’t Know About the Jigsaw Method” (blog post)

- The Jigsaw Classroom Overview (webpage)

- The Teaching Channel “Jigsaw’s: A Strategy for Understanding Texts” (video)

- The Teaching Channel “Interacting with Complex Texts: Jigsaw Project” (video)

- Description of Reciprocal Teaching – Ideas for Roles in Group work

How to become a billionaire -OR- What’s authenticity got to do with it?

I remember watching my daughter learn how to ride a bike. I could not tell her with words how to do it, nor did she want me to interrupt her attempts with demonstrations. Instead, she needed to observe her sister and then go through her own process of trial and error until she figured it out. I remember a day when we were out practicing. She had a balance bike (a bike with no pedals), and up until that day she always kept one foot on the ground. I could see her hesitating in fear of falling. But this day was different. Her demeanor switched from fearful to determined. I watched her go in circles on a driveway with a slight angle over and over again, gradually taking bigger and bigger risks until she got it. She lifted her feet and balanced with the bike under her. That was the turning point. From that point forward, she was off the races.

I wish I could get inside her head at the moment to find the thing ignited her determination to learn that day. If I could, I’d bottle it and become a billionaire.

We don’t always know what will create that golden moment for a child, but I can see some conditions that may have helped foster it.

- Safety & Trust – My daughter knew she could take a risk because if she did happen to fall, I would be right there to scoop her up and kiss her boo-boos.

- Modeling – She watched her sister do it.

- Tools – I gave her a developmentally-appropriate bike and neighborhood to ride in. She self-selected a driveway with just the right “grade” for her to practice the new skill.

- Practice – I gave her time and space to test things out, to learn by trial and error.

- Praise – I acknowledged and praised her efforts to learn at various points in the process, and I praised the bologna out of her when she got it.

- Togetherness – This was a family event. She wasn’t flying solo. We were learning something but also enjoying one another’s company.

So, back to the title of this tip, “What’s authenticity got to do with it?”

In PBL (Project-Based Learning) authenticity is heralded as an essential element for a gold-standard project. However, sometimes authenticity gets narrowly defined as something with a “real world” connection. For example, we are learning about estimation in math, and now I can estimate my total bill at the grocery story in order to stay within my budget. Essentially, it’s the place where students can apply their learning. I believe it can be helpful for students to understand how what they are learning can be useful in “real life,” but sometimes this “real life” connection feels so forced that it doesn’t really bring learning forward.

So, I’d like to expand that definition authenticity to include the extent to which is the process of solving a problem/puzzle, creating a product/performance, or mastering a skill is “owned” by the learner. Real learning takes place when the learner is motivated to engage in the productive struggle necessary to grow new brain cells! It is satisfying to struggle through new and challenging content, and then eventually gain mastery of that content.

What are some shifts we can make in our learning processes that will better enable students to take ownership of the learning? Here are a few ideas. Please add more in the comment section!

- Safety & Trust: Students won’t take learning risks if they are too afraid. Create conditions in your classroom that generate trust. Attend to the physical and social-emotional of your learners. Use reflective / meta-cognitive journaling, discussions, and/or check-ins throughout the learning activities, so students learn to attend to their own needs, too.

- Modeling: Provide students with exemplars and rubrics. Let them examine and process them using active learning strategies.

- Tools/Scaffolds: Don’t use a “one size fits all” approach. Offer a wide variety of tools and supports for learning and then help students to self-select the right tool for that moment in their learning process. Help student evaluate their choice of scaffolds and to recognize when they no longer need a scaffold, too. (Over-scaffolding and unnecessary rescuing send the message that you don’t believe they can do it on their own. Students need to engage in productive struggle to grow their brain power!)

- Practice: We learn more through failure than through success. Offer many opportunities to practice, get feedback, and then practice again.

- Praise: Students need a support and genuine acknowledgment of their efforts and achievements.

- Togetherness: Collaborative structures make learning meaningful not just because of the content but also the positive relationships that can be fostered through group learning.

By the way, if you figure out how to bottle that determination I talked about earlier, I get a cut, right? Just sayin’.

Are my students actually learning?

I remember my second year teaching. A teacher showed me the pacing guide for the curriculum and said, “If you just teach all the stuff in the color red, you will have covered all the 7th grade standards.” At this point in my teaching career, I had no teaching credential and I wasn’t very familiar with standards. I was relieved to have a cheat sheet to get me through. I knew what we would be doing each day. I had a plan. It went pretty well, but when I got to the end of the year, I thought, “Did my students actually learn anything?” I honestly had no idea.

Fast forward to my interview to work at Napa High. We were discussing how I would create lesson plans and implement them. One interview question I distinctly remember was, “What do you do for the students who don’t get it?” Pause. Silence. I was searching my brain for the right answer, but I had nothing. So, I replied, “I don’t know. Do you have people here who can teach me that?”

I got the job.

Sometimes we get so caught up in making sure we fill the minutes and days with activities, that we forget to make sure we know (and our students) know what they are actually learning.

Last year, I began to tweak my teaching practices by spending a lot more time in my planning process considering my exact learning objective for each lesson or lesson series, and then trying new ways of communicating that goal my students. With greater clarity came more focused lessons, higher student engagement, more actionable feedback on learning (not just completion of activities), and a stronger culture of learning in the classroom. It was not perfect, but it was better.

It’s a lot like the Visible Learner Protocol we have been using at our site.

- What are my students learning? This is not their current project, the driving question, the theme of the unit, or the graphic organizer they are filling out. These are the standards-based, measurable knowledge and skills I want them to learn.

- How do I know and how do they know when they have learned it? I want to break the learning up into discrete chunks at various depths of knowledge and provide clear feedback along the way, not just on the test or at the end of the unit. I want my students get frequent feedback on their progress toward the learning goals. Part of my job is to help students recognize the gap between what they already know and what I want them to learn. I want to offer sufficient scaffolds for students who are struggling and sufficient challenge for those who have enough proficiency to take the next steps in their learning.

- What do students do if they get stuck? What do I do as the teacher to support them through the learning process? This is where I am building student capacity for independence. How will I create and manage a classroom culture of learning and support, so that students have the skills to climb out of the learning pit? I want students to be focused on their mastery of the learning objective, not just completion of a series of assignments.

Part of what I learned at Napa High was that I could reteach material to students who didn’t get it the first time. This was not the “work completion” model I had previously been using. My focus slowly shifted from making sure all the students did all the work to making sure all students reached the learning target or objective. I believe that shift has helped me become a stronger teacher and I am grateful for the teachers who showed me the way.

ELPAC Prep – Reading!

The testing window the the ELPAC opens in February and we are gearing up to give the test to our English Learners!

All English Learners take an annual state test to measure their language development – Reading, Writing, Listening and Speaking. This test used to be called the CELDT; now it is called the ELPAC. Annual testing was previously conducted in the fall, but the ELPAC is now administered in late winter / early spring. The ELPAC aligns with the 2012 ELD standards. This is the second year that the ELPAC Summative test has been fully operational.

After looking at last year’s test results, we realized that we need to focus on preparing students for the Reading domain of the test. The reading section includes informational texts, a literary passage, and a “student” essay. Students need to determine the main idea, evaluate evidence, and make inferences. Vocabulary in context is also tested in this section.

If there is one change I would make when teaching my core ELA classes, it would be to be more intentional and purposeful how I incorporate vocabulary development — including teaching students how to use context clues and word parts (affixes and roots) to predict meanings, and how to use a dictionary or thesaurus to evaluate those predictions. Students need to know what to do when they encounter unknown words, especially multisyllable words, so that they have the tools they need to independently build their personal lexicons. I would be more intentional about creating independent learners who are “ready for rigor,” as Zaretta Hammond puts it.

Additional Resources

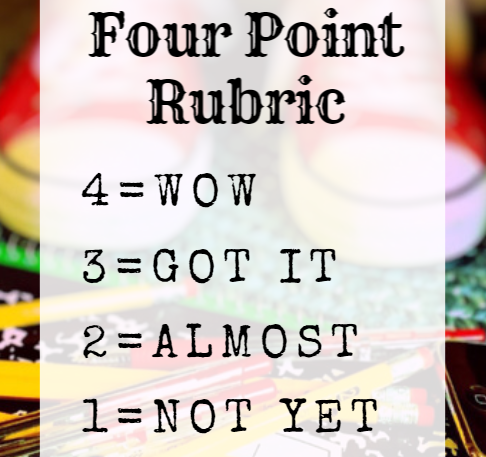

Four Point Rubrics Changed My Life!

With winter break just around the corner, I hope you don’t have piles of student work to take home and grade! In years past, a least some of my winter break has always been spend grading student writing. How do I grade my students who are English Learners, especially since they are not writing at grade level proficiency (which is why they are still designated as ELs)?

Grading practices for English Learners is one piece of the much bigger feedback picture. First, grading English learners in an equitable manner begins with teacher clarity around learning objectives and outcomes. English Learners can make measurable progress toward clearly defined content and language objectives. We have to give them a clear target at which to aim! Second, once we have clarity, we can design and implement scaffolds that make sense for the particular objectives we have chosen. Third, we can give students multiple opportunities and modalities for demonstrating their knowledge and skills, coupled with high quality feedback, so they know how to improve. Fourth, we give students grades in the grade book and explain how those grades relate to qualitative descriptors of their progress towards learning goals.

I teach my students to think of of letter grades (A-F) and rubric scores (4-0) as corresponding to the following qualitative descriptors:

A/4 = Wow; above the standard

B/3 = Got it; met the standard

C/2 = Almost; basic; below the standard but showing a basic understanding of concepts and skills

D/1 = Not yet; below basic understanding, but some growth and/or effort demonstrated

F/0 = No understanding of basic concepts, no growth or effort demonstrated, incomplete or missing

In grade level ELA classes, most of my students who are English Learners can and do get Cs and even Bs. Based on the way I grade, it is really hard for them to get As, but it also rare for them to get Ds or Fs. I want my grades to give students honest and accurate feedback on where they are in relationship to the goal of proficiency.

Grades in the gradebook lead to very little student growth, in my opinion. Low grades can discourage students from making an effort to learn, although sometimes zeros or Fs on assignments can motivate students to turn in work. Chronically having Ds and Fs with no hope of recovery kills learning. Students with Ds and Fs need to know that you are on their side and want them to succeed. They need an achievable plan for raising their grades, or they might give up on a class completely.

In my experience, the practice that leads to substantial student buy-in and growth is conferencing with individual students and letting them be part of the process for assigning grades and rubric scores to their own work. High quality, timely feedback on progress toward a clearly defined objective is really effective for helping students to learn. (See Hattie’s work on the effect size of feedback on learning.)

What questions or issues have you experienced in your grading of English Learners? How have you resolved these questions?

For more about grading English learners, I recommend this article called “Five Pillars of Equitably Grading ELLs.”

For more on feedback, I recommend this resource called “Essential Practice: Provide Effective Feedback.”

Learn Their Stories Part 2

On Monday, right as our after school math intervention class was getting started, the fire alarm went off. Since we were evacuated to the field, I got a chance to connect with a few students, which always make me happy. (I teach because I love students!)

I noticed a tall, older-looking student, and so I asked him if people think he is in high school. He laughed and told me how people often think his is at least 18 years old. After that our conversation went something like this:

“Yeah I was held back a grade in elementary school because I started school in Mexico. Like, I was born in the U.S., but my mom need to back to Mexico to fix her [immigration] papers.”

“So you went with her?”

“Yeah.”

“How long did you live there?”

“I went to kindergarten and first grade in Mexico.”

“Oh, so when you got back to the U.S., you got held back?”

“Well, those grades, kindergarten and first grade, are when you first learn how to read, so I was behind when I got here. So that’s why I got held back.”

“Huh. Do you feel like you have been able to catch up since then?

“Well, I was really good at math. That was like my best subject and reading was hard. So then I focused so much on reading that I got behind in math. Now I’m just trying to get balanced in both.”

“Well, after school intervention seems like a good place to start.”

“Yeah, we just had a meeting about it and I am just trying to get my grades up in everything.”

“Cool. Hey, thanks for talking to me.”

I found this student to be phenomenally self-aware, but I was a little sad that his story didn’t seem to include the feeling that his experiences were an asset. I mean, he’s had a rich life experience! He’s gone to school in two different countries and learned two different languages! Now, I don’t want to downplay the challenges that he has encountered, but I would love for him to recognize and value how those challenges have shaped him, pushed him, and helped him to grow more resilient.

He had a story that he wanted to tell. It didn’t take a lot of time or prompting to help him to tell it. Hearing his story changed my perception of him and made me appreciate his choice to attend an after school intervention class in a much deeper way.

As a beginning teacher, I remember feeling really pressured to keep students on task all the time, and to leave little room for side-conversations or chatter. But now, as I weave my way around classrooms, I realize that relationships are everything. If I take just a little time to listen, ask questions, and build rapport, it makes a huge difference in how much effort students are willing to put into the work I am asking them to do.

For example, if a group of students is off task, I listen for a few seconds before interrupting. Sometimes, they will redirect to the task without any prompting. Sometimes, I join the conversation by sharing something about myself that connects to their conversation or by asking a few questions to learn about them before I ask my “refocus” type of questions. I learn a lot when I take a little time to listen.

Usually, my refocus question is, “So, what are you working on?” I lead with questions rather than directives. Questions invite students to explain their progress, their learning, their questions, their needs. . .and their stories.